Imagine the following scenario: You have arranged to go for a bike ride with a woman from an online dating site. The date was organised on the back of a few laconic messages: too narrow a set of observations to make any viable predictions of each other’s personalities, idiosyncrasies or foibles. During the bike ride, do you:

- (A) Drop (or at least attempt to drop) her from the outset, pedalling as fast as possible, thereby both wooing her with your athletic prowess and telling her you mean business.

- (B) Cut all the red lights and cycle against traffic, thereby demonstrating you are a ‘bad boy’ that plays by nobody’s rules; not even your own.

- (C) Turn up with stabilisers, a full-face helmet and body armour, intimating that you are a cautious, prudent man, who will make good father material.

- (D) Turn up in a Harley-Davidson, for neither of you specified what type of ‘bike ride’ this would be; thereby dazzling her with your imagination and mental flexibility, if not your green credentials.

- (E) Be yourself

- (F) Make massive, unjustified generalisations about someone’s temperament based on a limited set of observations.

Online dating; as opposed to its ostensibly more organic counterpart of meeting through friends, work or hobby group; seems to be based on answer ‘F’. You extrapolate a rich, complex psychology from a mere snippet of information. Tinder is even more culpable of this. Consider the utterances of my female friend:

“Oh, none of his three profile photos are of him with other people – he must be a loner.”

Err… did you ever consider that the intention of a profile picture is to allow its recipient to see what he/she looks like, not what his or her mates look like.

“Oh, none of his pictures are of him posing monotonously atop Machu Picchu – he must be dull, monotonous and lack curiosity about the world.”

Oh for God’s sake. Surely a photograph of someone contains too little data on which to judge the size of their carbon footprint? But, if it’s any defence of my friend’s superficiality, we are all guilty of doing similar things: at least implicitly.

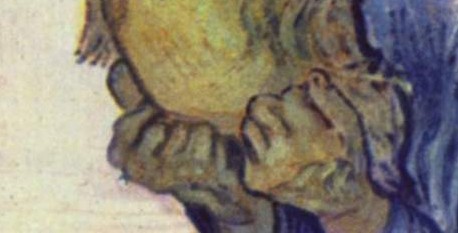

According to a study by Todorov et al (2005), we judge people with soft faces, round chins and higher foreheads to be trustworthy. Those with wider noses and protruding chins are deemed dominant. Fine, so we all form elaborate tapestries of people’s personalities based on seemingly shallow grounds – their tone of voice, their Tinder photo, their manner of riding a bike. Yet, when it comes to dating, does personality even matter in the first place?

To the practitioner of Tinder, surely personality is second fiddle to appearances? I’ve never heard a man exclaim,

“Wow, look at the traits of impulsivity on her!”

Numerous analyses have told us that we assortatively mate for physical attractiveness, ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Disgustingly beautiful people marry other beauties. Chinese people marry Chinese people. High socioeconomic status is considered desirable across cultures. Recall the immortal words of British comic, Mrs Merton, to magician’s assistant, Debbie McGee:

“ So, what first attracted you to the millionaire Paul Daniels?”

There is no mention of personality. Even academics are conflicted on the importance of personality and temperament when it comes to choosing a mate.

Anthropologist Helen Fisher thinks personality is important. As with most things psychological, personality is a product of nature and nurture; hardwiring and life experience; or, to adopt the academic labels: traits of temperament and traits of character.

Traits of temperament are associated with genes and seem heritable across generations. Different traits of temperament may be grossly subserved by the brain’s various neurotransmitter systems. Moreover, such traits remain stable across one’s life course. Can people change? Yes, but not so much their temperament.

Contrast this with traits of character; sculpted through life experience. That time your mother scolded you, that time you shat yourself in class, that time that girl jilted you; all these experiences will no doubt shape who you are today. Let’s get back to temperament. Fisher (2004) proposes that people generally fall into one of four categories, based on their predominant traits of temperament:

- Explorers – tend to exhibit impulsivity, seek novelty and new experiences, are intellectually curious and mentally flexible, but tend to lack introspection and are easily bored. They may be more prone to addiction. These traits are associated with the dopaminergic neurotransmitter system.

- Builders – are more likely to conform to social norms, obey rules and authority, exercise self-control and are cautious. If I’m being honest, builders sound like boring twats. Yet, I suppose this dullness is mitigated by their conscientiousness, creativity with numbers, reduced susceptibility to anxiety and ability to form close friends. These traits are associated with the serotonergic neurotransmitter system.

- Directors – have deep, narrow interests, a good understanding of rules-based systems such as mathematics, computing or music and good visuo-spatial skills. In what, to me, seemingly resembles autism-spectrum type traits, directors unfortunately also tend to have less social nous, empathy, emotion-recognition skills and verbal fluency. These traits are associated with prenatal/ in-utero exposure to testosterone.

- Negotiators – seem to possess the obverse set of traits to directors. They are characterised by good empathy, theory of mind, linguistic skills and a generally prosocial attitude. As opposed to small details, negotiators tend to focus on the bigger picture. These traits are associated with pre-natal/ in-utero exposure to oestrogen.

So we can grossly divide people into temperament types. What bearing does this have on mate selection? Birds of a feather flock together. Or, less eloquently but semantically equivalent: shit sticks together. The sentiment of both these statements is that ‘like attracts like’. Crudely basing a scientific hypothesis on scatological clichés, one would expect explorers to pair up with other explorers, directors to pair up with other directors etc.

Yet, equally widely espoused is the notion that, like an anion and a cation, opposites attract. So, now we have an alternative hypothesis – people may be attracted to those of a different temperament type. In her analysis, Fisher evaluated the temperament type of 28,000 people on an online dating site, before sitting back and observing how they paired up. She actually found a mixture of both patterns:

- Explorers (characterised by novelty-seeking and impulsivity) had an affinity towards other explorers. In other words, birds of a feather flocked together.

- Builders (characterised by caution and adherence to rules) had an affinity towards other builders. Shit, in other words, stuck together.

- But, negotiators (typified by empathy and good social skills) disproportionately paired up with directors (a group marked by analytical thought and decisiveness). Opposites attracted.

To a scientist, or any person with enough intellectual curiosity to peel themselves away from whatever cerebrally-noxious reality television show is searing their neurones at the time, the next question is why? Or, more accurately, wherefore? Why is it the case that explorers like similar temperament types, but negotiators and directors like their opposite types?

The answer, according to Fisher, is that such pairings represent stable parenting strategies for raising young and perpetuating one’s genes. The negotiator’s social prowess and empathy apparently complement the director’s analytical and decisive mind, making them a solid parenting base.

Two builders arguably can form wide supportive social networks and a strong, loyal parent base from which to raise offspring. Their temperament style is probably suited towards a long-term, strong relationship, which is a viable reproductive strategy for maximising inclusive fitness – that is, ensuring your genes are passed on (in this case by rearing healthy offspring).

Conversely, explorers, with their impulsive and risk-taking traits, are more suited to a short-term mating strategy. By having a series of short-term relationships, they can spread their genes far and wide and maximise inclusive fitness that way. (Ejaculating on the assembly line at Tampax’s factory would seem a more efficient way of spreading one’s genes, but apparently tampons weren’t invented when modern man was evolving).

Now recall the question posed at the start of this piece. The answer is clearly contingent upon the temperament type of the partner you are trying to romance.

You can either be yourself and hope she is of a compatible temperament type; or, more shrewdly, make a massive judgement of her temperament in a few seconds and then adjust your behaviour accordingly. She has a red streak in her hair – she must be impulsive. An explorer. What goes with explorer? Another explorer of course! Quick, better snort a line of coke in front of her and then make a load of risqué Jimmy Saville jokes.